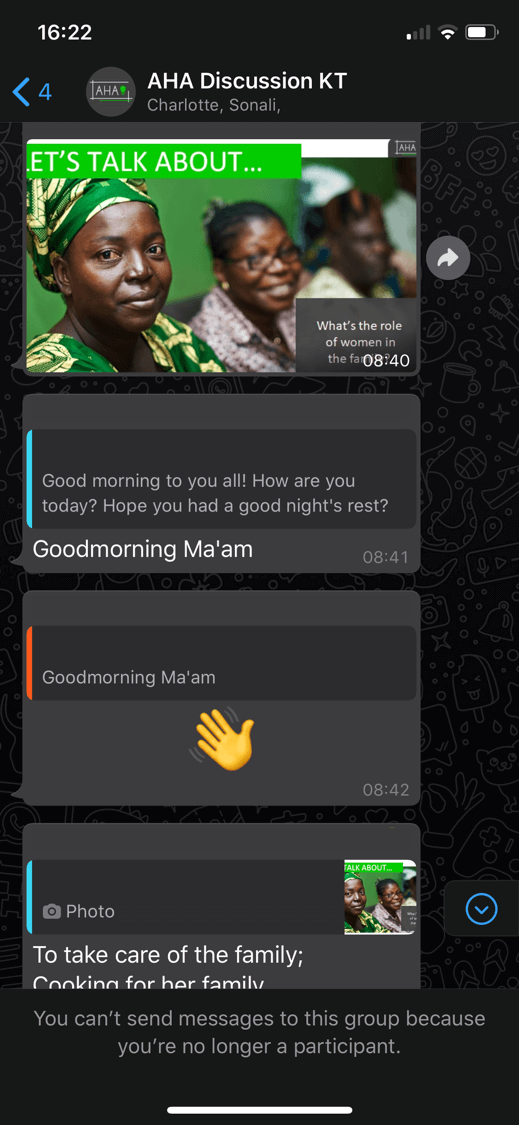

We learned a lot about how to maximise it as a platform too. We spoke to our respondents in groups; this felt familiar, and most like a ‘normal’ group chat, where there’s no pressure on anyone but everyone is welcome to speak.

Dialogue flowed best with a constantly-moderated stream of probes and new questions, and use of the Reply function to specific messages, for clarity of what was needed from who. Even with conversation in English, regional moderation was necessary, to know where to push and where not to. There were tasks that worked better, like self-shot videos, which told us a million things very quickly. The Google Images collage task we set told us nothing – because everyone draws from the same bank of pictures, and it was harder to gauge what aspects participants felt different images communicated. Our two-phase process was invaluable, allowing us to re-focus for the second stage on just the most compelling aspects from the first.

Of course, there are limitations, particularly in terms of digital skew. We can pay for people’s mobile data to thank them for participating, but not everyone (especially women) has an internet-enabled phone and the ability to use it. That said: internet penetration is predicted to be 84+% in Nigeria by 2023, so it’s an evolving situation. And for many of our clients, the audience we spoke to would be the primary opportunity.

Plus with WhatsApp specifically, privacy is a pain. It’s encrypted, but hiding your number from others in a group is, so far, impossible (however many YouTube videos we watched which promised to do this). There are workarounds, like broadcast mode or a Business page, but they would lose the group experience. We made sure respondents were aware of that in advance and gave fully informed consent – and in our case, many used WhatsApp for sales and were accustomed to having lots of numbers in groups, so it wasn’t a problem. But elsewhere it could have been. There are other apps, but they’d be less familiar.

Analytically too: WhatsApp definitely isn’t designed for sorting through many people’s responses.